By Nicole Thompson in Toronto

Canadian fashion companies that are pushing back against a market that expects loads of cheap clothes say keeping operations small and local is the key to sustainability, but so too is the need to inform the public about the consequences of fast fashion.

Ahead of the 10th annual Canadian Arts and Fashion Awards on Saturday, homegrown retailers at the forefront of an ethically-minded movement say they're increasingly focused on changing consumer expectations driven by quickly made clothing.

"It's just a fact that humans are consuming at a fast pace and consuming a lot of resources and energy," said Jean-Philippe Robert, president of the Montreal-based outerwear company Quartz Co., among several brands nominated for a sustainability CAFA.

"We have to limit ourselves. Fashion is a polluting industry; it's a known fact. But at the same time, people need to dress."

It may appear to be a counterintuitive stance for a company that relies on people purchasing products, but Robert said it's fundamental to his personal philosophy.

"We design with the philosophy that products need to be built to last. For us, sustainability is not only the materials, but also how you approach the design so that people can wear the product for many years, and when they're done or their taste changes they can give it to someone or sell it," he said of his company, known for high-quality outerwear made of recycled materials that are guaranteed to last a lifetime.

"The goal here is to make products that have a certain longevity and a certain quality to them."

Nominees for CAFA's sustainability award include fellow outerwear company Adhere To, clothing and home decor brand Kotn, swimwear maker Londre, jewelry giant Mejuri and denim designer Triarchy.

Robert said Quartz Co. focuses on high-quality materials and careful construction. Each product is inspected for quality control and the company offers a free repairs program for damage that's not eligible for replacement.

The company produces fewer products than fast fashion retailers, many of which launch a new line on a monthly or weekly basis. In the case of ultrafast online marketplace Shein, the world's largest clothing retailer, hundreds or thousands of new products are posted daily. Like Shein, cheaper Amazon-alternative Temu also ships directly to consumers from manufacturers, no in-between warehouse necessary.

Quartz Co., Robert said, drops a new line roughly twice a year with only 12 or so new styles each time.

Everything is designed in-house and made locally — unlike many fast fashion retailers, which source their clothes from an array of marketplaces and wholesalers and seldom have close relationships with manufacturers.

But all of that leads to a higher price tag, Robert noted. Quartz Co. outerwear start at $400 for a lightweight quilted jacket, and max out at $1,550 for a parka — roughly 10 times the price of similarly labelled products on Shein.

"I'm confident that even among some of those whose budgets are lower, some of the current Shein and Temu buyers will eventually change their behaviour and save for better pieces and end up buying less," Robert said.

"It's probably as costly to consume in a fast fashion way and have clothing that you have to get rid of quickly rather than buying more expensive pieces that will last a long time."

The sustainability push extends beyond the brands nominated for CAFA's sustainability prize.

Eliza Faulkner, the designer behind the eponymous fashion house nominated for best womenswear company, said she also keeps production runs small and makes products locally — her ultrafeminine designs — from voluminous dresses to bow-adorned shirts — are made just across the street from her Montreal HQ.

Both Faulkner and Quartz encourage their customers to keep wearing their products rather than buy more, and have sections on their websites outlining their sustainability initiatives.

Local manufacturing started out of necessity when Faulkner launched her brand 11 years ago, Faulkner said, because offshore factories required larger production runs than she was prepared to order.

At the time, she was making 20 of each style, she said. Now, she maxes out at about 500 of a style in a single colour, but as her brand grew, she opted to keep things local.

"It's just really nice to have that control and be able to talk to the people that are making it," Faulkner said.

"It's just about creating something that's really good quality and beautifully made so that you will keep it forever," she added.

Also nominated for womenswear designer of the year are Hilary MacMillan, Lamarque, RVNG Couture and Silk Laundry. Menswear nominees are École de Pensée, Frank And Oak, Raised by Wolves and Section 35.

Dirk de Waal, an assistant professor of fashion at Toronto Metropolitan University, said it's important for companies and consumers alike to think about what sustainability really means.

It goes beyond environmental impacts and should include the human cost of fashion: the effects on workers, on the economy.

"We usually just go to environment, but what about the people? What about the cultures? The fashion industry has become this machine of overproducing to feed our addiction to shopping."

Consuming less, he said, is key to all areas of sustainability.

"We need to understand that the garment — the actual garment — is not the problem. The consumer is the problem," he said. "We don't value clothes the same way that we used to. We buy something, wear it maybe four or five times and throw it away because it's now not cute enough anymore."

Companies see the money-making potential in that desire for product, and make more and more items for cheaper, sacrificing quality, de Waal said.

Fashion houses hoping to prioritize sustainability have to resist the temptation to capitalize, he said.

"Can we think about the impact that we can have on communities? Can we think about the well-being of society, the well-being of the planet, and not just about growth?" de Waal said.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 13, 2023

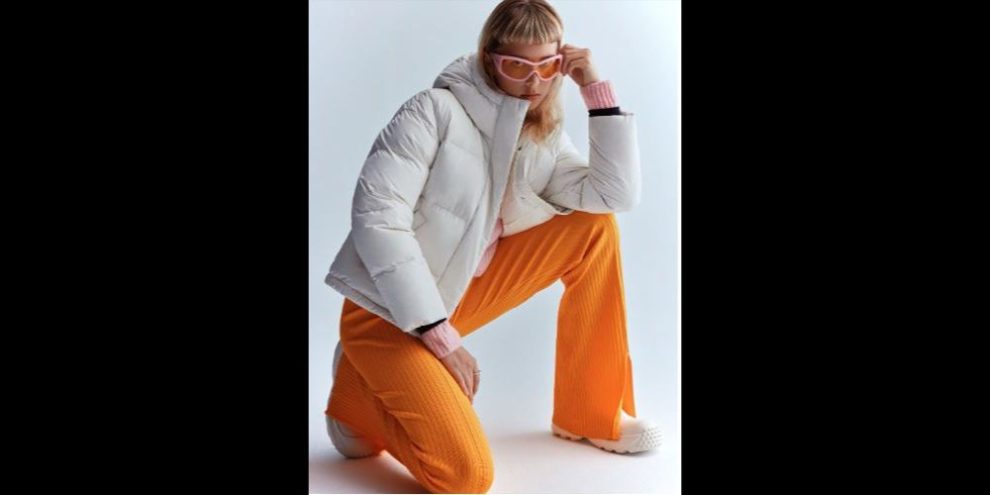

Banner image via The Canadian Press