She was just 21 years old when she won Hollywood's most coveted prize – the Oscar, for Best Actress – for her first movie, "Children of a Lesser God." "You have to understand that I was a girl from Chicago who appeared on the scene out of nowhere," said Marlee Matlin.

Thirty-four years later, she remains the only deaf person to win an Academy Award, in any category.

"When I won the Oscar," she told Turner Classic Movies host Ben Mankiewicz, "the community was very, obviously very thrilled, certainly. And then they said, 'Okay, now what? What are you gonna do for us?' It was a heavy load."

Her new film, "CODA," now streaming on Apple TV, is the story of deaf parents with two children, a deaf son, and a hearing daughter, played by Emilia Jones.

Matlin plays the mother: "It's about a hearing girl who wants to sing, but she has deaf parents who rely on her to interpret, and they always have."

Mankiewicz asked, "They want hearing actors as the father and the older brother. And you say?"

"I said, 'If you do that, if you choose somebody who's gonna 'play' a deaf person, I'm out,'" Matlin replied.

"That suggests to me that, maybe, 35 years after 'Children of a Lesser God,' and 34 years after the Oscar, that you're a little more comfortable making some noise?"

"And in all honesty, I didn't even think," Matlin said. "I just said it, I put it out there. Playing deaf is not a costume. We, deaf people, live it."

For Matlin, "CODA" (the acronym stands for Child Of Deaf Adults) gave her a rare opportunity to work in an ensemble cast of deaf actors.

"It was always sort of as background or, you know, token deaf characters," Matlin said. "And this time we carried the film."

"I was envious, and I think my wife was, too, of the marriage [in the film]," Mankiewicz smiled. "Like, that's what I want, right? That was it. That's as good as it gets!"

"You could still do it," Matlin laughed.

"No, we're good, we're good," Mankiewicz assured her.

As the most famous deaf person in show business (and probably the country), Matlin has worked steadily since her debut – feisty on "The West Wing," funny in an episode of "Seinfeld," and always game, quickly becoming an audience favourite on "Dancing with the Stars."

She's come a long way from the Chicago suburb where she grew up as a deaf child in a hearing family. Her hearing loss was caused by illness and high fevers when she was just one-and-a-half years old. "My childhood was so normal," she said. "I was just so happy to have great neighbours, great schools, great friends, great family."

"You're a big sports fan?"

"Yes, I am. Big time! My father and I always watched sports together. You really didn't need captions to watch sports."

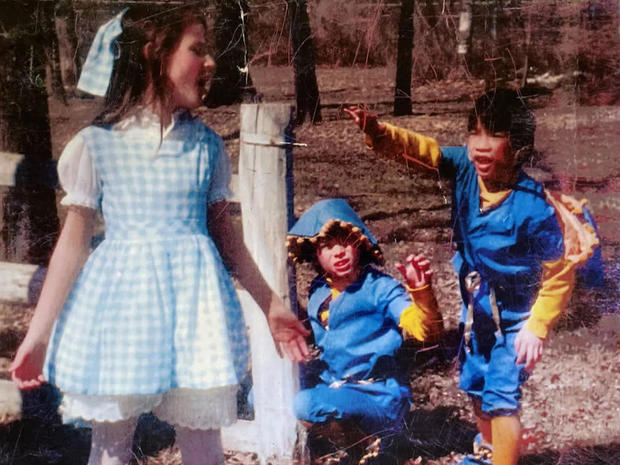

Her parents enrolled her in a weekend arts program for deaf children, where the camp director cast eight-year-old Matlin as Dorothy in "The Wizard of Oz."

Mankiewicz asked, "What do you think Dr. Pat saw in you that made her think, 'This little girl could be Dorothy?'"

"I guess she saw in me as a little girl who was very outspoken, who was very much of a people person, a social butterfly maybe. I don't know, or maybe she was just looking for a Dorothy. Who knows? I don't know. And she found a Dorothy!"

For this Dorothy, there was no place like the stage, and she owned it. And when Henry Winkler saw her perform at an arts festival for deaf kids when she was 12, Matlin found a lifelong mentor.

"He looked at me and he said, 'Marlee, you can be whatever you wanna be, as long as you believe in yourself in your heart,'" she said.

Winkler and Matlin stayed close. How close? Soon after she won the Academy Award, Henry and his wife, Stacey, invited her over for the weekend, to show off her Oscar.

She moved out two years later.

"Henry and Stacey Winkler are a godsend to me," Matlin said.

It wasn't an easy time in Matlin's life. The night she won the Oscar, she'd been out of rehab for a serious drug addiction for just 30 days. After the parties, she got into a limo with her Oscar and her costar and boyfriend, William Hurt.

"He didn't sit next to me; he sat across from me," she recalled. "He looked at me and looked at the Oscar. Looked at me, look at the Oscar. And he said, 'Do you realize how many actors have worked for so many years to get what you got, that little man, in one film?' And I didn't know what to say. I couldn't say anything."

Mankiewicz said, "You're newly sober, you're 21, you're in Hollywood, and you have this enormous high of the Oscar win – and then this devastating low of this man you love belittling you, on the same night. I just know it's hard. I know sobriety is hard for anybody."

"It is the hardest thing," Matlin said. "I still say to myself, one day at a time. I still do. But if Henry was not in my life, he and his wife both were the ones who held my hand, guided me, and didn't let go.

"And when I said I had to move out, Stacey said, the first thing she said, 'What did we do wrong?' I said, 'No, no, no, Stacey, I need to fly the coop. I need to grow up. I need space!'"

Today, Matlin's life is full, whether she's working or not. She and her husband, Kevin Grandalski, have four children. All hear.

Mankiewicz asked, "You ever feel isolated in a house with five hearing people?"

"I wouldn't say isolated, because I'm accustomed to it," Matlin said. "Growing up was the same thing. But yet, I always say, 'What did you say?' or, 'What are you talking about?' And they tell me. Probably the only difference from when I grew up."

Her son, Tyler, heads to college this week. His mom made sure to show him "CODA" before he left. "She was like, 'Hey, do you want to, like, watch a movie with me?' And I like, 'Sure, what movie?' She's like, 'Let's watch 'CODA.'"

"Did you note her watching you during it?" Mankiewicz asked.

"Yes!" Tyler laughed. "Every time she'd kind of come on, she'd kind of just look … And I'm like, 'You're doing great. Don't worry,' you know?"

Marlee Matlin may be doing great, but there's still work to do.

"I look forward to more opportunities," she said. "And not just me, but for deaf actors, writers, directors, people who work behind the camera. We have a history, we have a culture, we are part of the diverse continuum. So, what do I do? I talk about it, I make noise about it."

"It feels like you're more comfortable with making noise now than you've ever been?" asked Mankiewicz.

"I'm more comfortable talking about what needs to be done," she said, adding, "I'm more comfortable talking about what should not be done."

Thank you to interpreter Jack Jason.

feature image: CBS News